Toxic Things

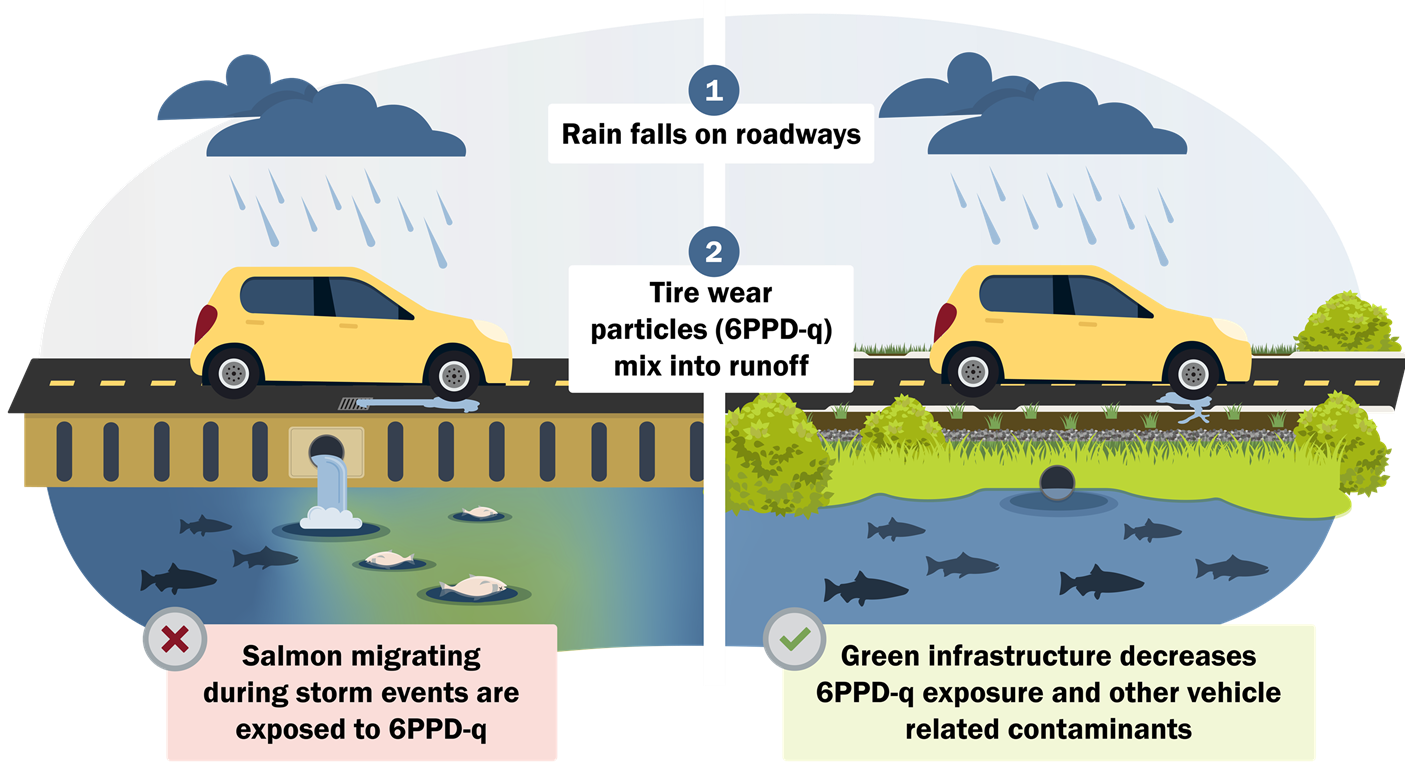

I’ve done what I can: the EV, the heat pump, the heat pump dryer, the induction stove, plus sealing the cracks around doors and windows. I can’t have solar panels because of tall cedars and hemlocks creating too much shade, but there is no fossil gas on my property anymore. I should be happy enough that I’ve done my best, and I was... until I went to a lecture by Dr. Edward P Kolodziej, a professor at the University of Washington, about a terrifying chemical called 6PPD. He and his team in Tacoma, Washington found that this chemical rapidly kills coho salmon in streams after heavy rainstorms.

And the cause of this carnage? Vehicle tires… everyone’s, everywhere. Car tires. Truck tires. Airplane tires. Bus tires. Probably bicycle tires, too. They all contain 6PPD, which becomes 6PPD-q when it migrates to the surface of the tire and reacts with ozone in the air, keeping the rubber from cracking prematurely. As tires hit bumps in the road or squeal against the pavement when brakes get slammed, small rubber particles break off and lie in wait on roadways—like a silent assassin—until they are washed into streams during heavy rainstorms. Unfortunately, there are no safe alternatives, yet.

According to Dr. Kolodziej, “6PPD-quinone is one of the five or six most toxic compounds to aquatic organisms ever identified. So, its impacts go far beyond just salmon.”

We don’t know why it is killing the coho (and also some trout), and what other species (including us) 6PPD-q presents a danger to, but the research to replace this chemical may take years or decades, since it has just begun.

In the meantime, my desire to drive a car guilt-free from carbon emissions is shattered because now a different pollutant is escaping from my tires whenever I get behind the wheel to go somewhere. So, I’m not at all done with guilt.

And why should I expect to be?

Just by being alive, I create pollution. There is no way around it. Even though I live a simpler lifestyle than many in the U.S., I still use more resources than billions of people in the developing world because I have more things. Things require energy to produce, to sell, to own, creating carbon emissions. Sometimes these things, such as tires on cars, can be toxic, but even our relationship with all our things has become toxic in many ways. Our relentless pursuit of material stuff leads not only to mammoth carbon emissions, but also broken lives in a rat-race world, which is the premise of the book called Love People, Use Things.

This isn’t a climate change book, but it is relevant to emission reductions. The book is written by two men who call themselves The Minimalists. Joshua Fields Millburn and Ryan Nicodemus have a blog, a podcast, and have made some films. I've only read the book, though, which begins with a chapter on how to live with less. They start with what they call the No Junk Rule—Everything you own can be placed in three piles: essential, nonessential, junk. The goal is to reduce as much of the nonessential and junk things in your life that you can. This decluttering, as they call it, helps people to step beyond the stress and financial burden of acquiring more than they need. And once they are free of that pressure, the book explains, people have the time and energy to change their relationship to themselves and close any fissures in their life between them and others. In essence, this is a self-help book, but if more people would at least begin with that initial decluttering of material things, it could reduce emissions. And then by subsequently healing their relationships, they may defeat the impulse to try to fix their loneliness and unhappiness through over-consumption.

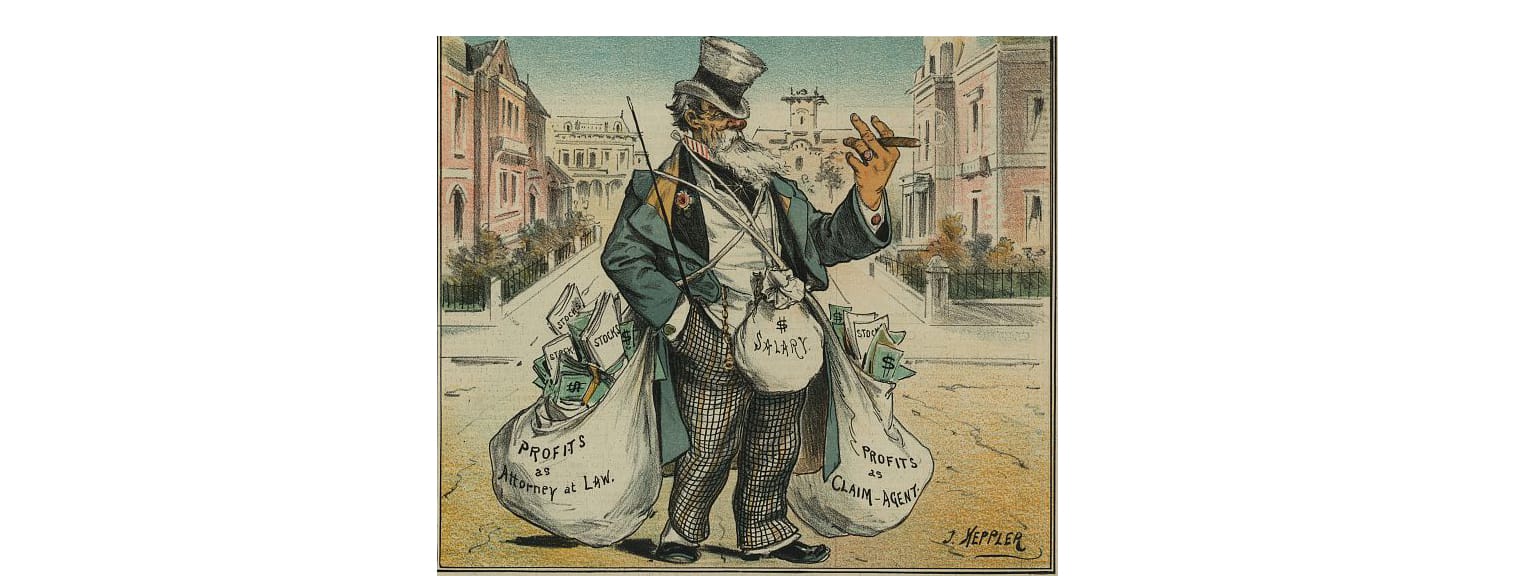

Throughout history, especially modern history, people have been chasing after things, and also chasing the money to buy those things, hoping to find gratification and acceptance. Now we see how that is ruining the planet by plundering resources and destroying our precious climate using copious amounts of fossil fuels. It is causing disaster, heartache, and species extinction. We must certainly let go of toxic things like 6PPD-laden car tires (when we can find a replacement chemical), but we must also let go of acquiring too many things, which becomes toxic to leading a satisfying life on a sustainable Earth.

And that brings me to my current thoughts about climate fiction. Is there a more expansive way to look at this new genre? Love People, Use Things is not a climate book, yet in an indirect way, it really is, so when I broaden my perspective a bit, I can see that many of the stories I've written over the years have been addressing climate change by focusing on emotional growth and pro-social development, especially in young people. While my climate fiction mystery, The EarthStar Solution, tackles climate action directly, another novel, How to Be a Dragon… without burning your tongue, is a coming-of-age story whose protagonist struggles to choose between anger and love. This story acknowledges the swirl of emotions inside young adult readers, and if it helps them mend their relationships there's a chance it might also lead them to healthier, less consumptive lives.

I've written many original fairy tales. They promote climate-saving behaviors too. Tales from the Dragon’s Cave… peacemaking stories for everyone and my picture book Dragon Soup are focused on conflict resolution. Wars and violence can create extreme amounts of carbon emissions either directly, with all the destruction, or indirectly, traumatizing people, leaving them emotionally wounded and possibly craving external fixes for their pain like possessions or money. Even my esoteric tales in When Dragons Cry For Mercy: And Other Tales of Inner Magic point people toward finding meaning in life, which can curtail their pursuit of too much stuff.

So though I concentrate on creating climate-focused fiction in my posts, any story that helps people connect with themself and others will boost our efforts to heal our climate through reducing consumption. And if you combine that healing story with climate action in a novel, it becomes an even more powerful form of climate fiction.

Joshua Fields Millburn writes:

“When we realize this—that we can use things without loving them, that we can treat our iPhone the way we treat our lip balm, as useful but not worthy of our love—then we are better able to understand real love, a love that is reserved for people, not the things that get in the way. It is possible to love people and use things, because the opposite never works.”

Member discussion